The Things That Haunt Me

My dad was charged with attempted murder, decades after he tried to kill my mom

One night when I was 13 years old, a face appeared at my bathroom window. I was getting ready for bed when I saw it: a round, moon-like thing that popped up from the darkness, illuminated in the glow of the house, features masked by the undulations in the glass block windows.

At first, I thought I was imagining it, until the face moved. I don’t remember ever being so scared as I was in that moment, slowly turning to glide past the face in the window, walking out of the bathroom and into the living room, where my grandmother was watching television.

“There’s someone at the window,” I said, to which she replied, “Of course there’s not, you’re being dramatic,” then made a big production out of dragging her legs over the edge of the couch, standing up, and walking into the bathroom to show me just how dramatic I was.

“See? There’s no one there,” she said gesturing to the now-empty window. She had opened her mouth to tell me I was seeing things when, just like that, the face popped up again.

“Go in your room. And lock the door,” she told me.

The police officer that came over later found nothing other than a footprint outside, though he mentioned a neighborhood boy had been caught doing this kind of thing in the recent past.

Looking back, it probably was just some boy, which doesn’t really make it less creepy but does mean that it wasn’t the one person my grandmother no doubt thought it was: my dad.

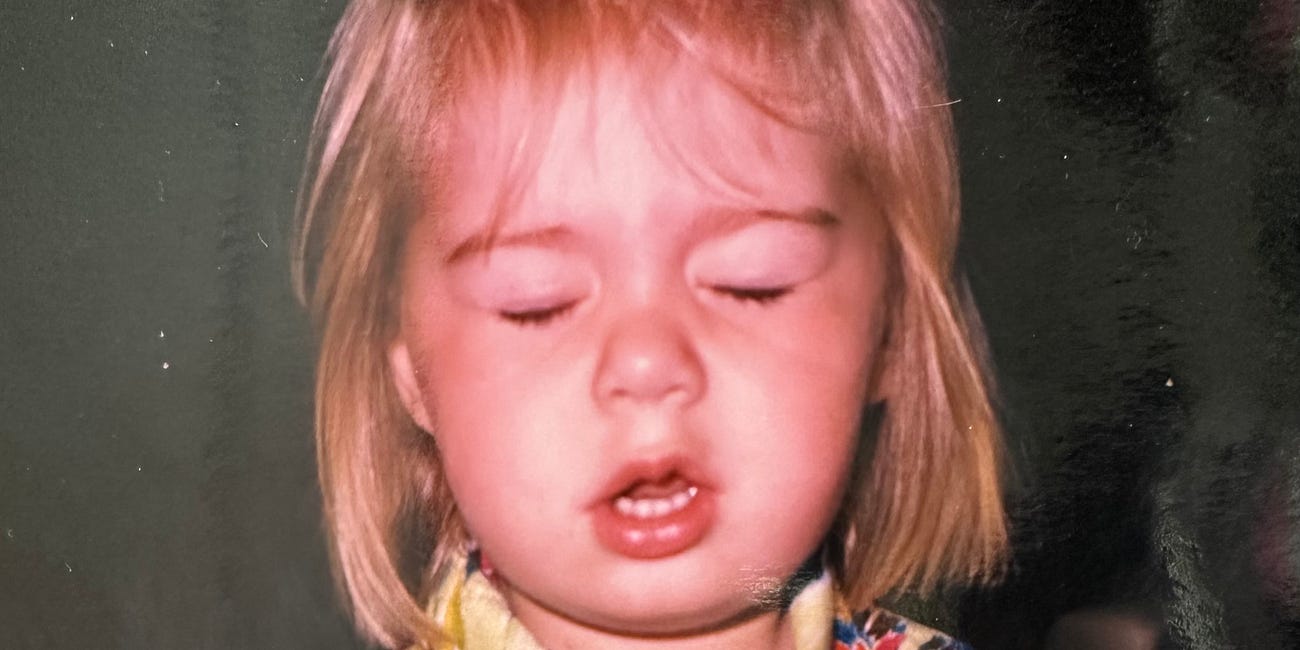

My dad was, for most of my life, merely a concept. He shot my mom when I was two months old, weeks after she left him and obtained a restraining order. He planned it out ahead of time, walking into a gun store with a friend to obtain the weapon, hiding in some brush in a parking lot near my grandmother’s house. He watched us pull out of her driveway, then he shot at the car — at my mom, and me, and my grandmother — twice. He struck my mom in the head on his second try. Following weeks in a coma and intensive care, she survived.

He was charged with aggravated assault which, in Georgia, can sometimes be used in lieu of attempted murder. The legal distinction lies in the intent and the nature of the act — aggravated assault typically involves causing serious bodily harm with a deadly weapon; attempted murder requires a specific intent to kill.

He was sentenced to two counts: aggravated assault, which came with a sentence of 10 years, and aggravated battery, which came with 20 years.

He got out in six.

I imagine my grandmother was notified when he was released in 1991 and, while she never outwardly let on that she was fearful, there were certainly signs.

Following my mom’s rehabilitation in a trauma center, the three of us moved to Florida, where my grandmother bought a piece of land in a gated community and drew up plans for a four-bedroom house. One of the bedrooms was built for me and it had no windows and a row of panic buttons installed in the wall. There was one button to call the paramedics, one to call the fire department, and one to call the police.

I never thought much of the buttons, other than that they must be in every home. And I never thought much of the lack of windows until I had slumber parties and everyone slept til noon (without natural light, you never know what time it is).

It was in the home with my windowless bedroom that the face at my bathroom window appeared. And while there was a brief glimmer of “was it him? did he find us?” it was exceedingly rare for me to ever even think about my father. I was never hamstrung by my fears of him, because he never felt real to me.

My grandmother took precautions, doctoring many of my school records so that I could go by her last name — Hollingsworth — and a shortened version of my first name — Ginny.

I was Ginny Hollingsworth until I was 18 years old, when I began going by what was always my real name, Virginia Chamlee, but what many assumed was some new identity I came up with on a whim.

I was Virginia Chamlee when social media and search engines became the de facto research method. That was when I first Googled him, out of boredom on a random Saturday afternoon.

A few clicks of a keyword and there he was — in a mugshot, staring blankly at the camera beneath fluorescent lights.

There was no pang of recognition. No “we share the same eyes,” or, “look — that dimple’s just like mine.” Just a mugshot of a rather unattractive man. The kind who looked like he would leer at me in a gas station.

And there, below the photo, was his incarceration history.

One would think that getting away with attempted murder might make you reformed — or, at least, appreciative enough of your freedom that you don’t take it for granted.

Not so, in the case of my father, whose resume included time served in 1980, 1982, 1985, 1994….

In fact, when I saw his photo for the first time, I noted that he was just about one year in to serving a 30-year sentence for trafficking amphetamine.

I made a mental note and took comfort in knowing that he’d probably never be free.

At that point, my grandmother had sold her house with the windowless room. No doubt the new owners had already broken through the plaster to let the light in.

I lived the first part of my adult life not thinking about my dad at all, really. I worked, I launched a successful vintage business, I traveled. Then my grandmother died in a car accident and I became the primary caretaker for my mom.

I started thinking about him a little more then, in the kind of way you might think of someone who threw a grenade into a room and left you to pick up the shrapnel.

Of course as I grew older, so did he, and so did technology, evolving to the point that it’s now much easier to find people — even to message them. Even if they don’t want you to.

Before my grandmother’s death, she had me set up a Facebook page for her furniture store — one that I rarely looked at, but still got notifications for, even five years after her death.

The first time I saw my dad had left a comment on the store’s page was in September 2024. “Beautiful furniture,” he wrote. “Reminds me of a girl I once knew.”

To a stranger on the internet, it would be innocuous but to me, it was a punch in the gut. It meant he was out.

The comments on the store’s page continued for a couple of weeks before I had the thought to check my mom’s personal Facebook page. Due to her injuries, she doesn’t often share photos of herself online. Her profile photo was, instead, the logo for my grandmother’s store, which meant he must have thought the store was hers. I deduced that the comments on the store’s Facebook page were a way to get my mom’s attention. My fears were confirmed when I checked her personal “message requests” — this purgatory-like folder that keeps notes sent by strangers in limbo, so you never actually see them unless you go looking.

He had written her dozens, spanning weeks.

“Are you secretly happy and excited to hear from me?”

“I really believe you have loved me since 1983.”

“Send me pictures.”

“Where does our beautiful child get her writing from? Or that high powered drive inside?”

“I love you. Hope you both are perfect. Give her an extra hug but don’t tell her it’s from me.”

“You moved on … I can’t and honestly I have no desire or intent to.”

So consumed was I by the thought that I somehow lucked out and escaped my father that I was shocked when I didn’t. There were no windows, but he still got in.

Some of his messages were crude, sexual, disgusting. In others, he detailed the shooting, moment by moment. In one, he said he was urging his friends to buy my book. In many, he swore he was sorry, swore he was changed.

Weeks later, he would try to kill another woman.

This is the part of the story that becomes almost self-referential. It’s an essay about an essay or, at least, what happened after I published one.

We never hit “accept” on the messages, and we certainly never responded, instead taking time to determine what to do next.

But on a Wednesday in October, I hit send on an essay here on Substack. The essay was not so much about him, but about the shooting and how I had worked to rebuild my life into something beautiful in the years that followed.

It was a nice respite from the fear, to bask in the kind messages and emails and comments I received in return. Maybe this is the whole point, I thought. Finding the beauty in something really ugly.

I felt optimistic about the situation even two days later, as I sat in a Vancouver convention center preparing to go onstage to discuss my tips for finding valuable things at thrift stores.

The “ping” on my cell phone alerted me to a message from my cousin. In it were two screenshots of a news article: Calhoun Man Suspected in Dalton Stabbing.

It was about a man who went to the store where his ex-girlfriend worked and stabbed her in full view of the customers. He then fled on foot and stabbed himself while police officers surrounded him.

It was about my father.

The woman he stabbed survived, following intensive surgeries. We’ve even been in brief contact on social media, bound as we are now by the invisible string of victimhood.

He survived, too, and was charged with aggravated assault, possession of a knife during the commission of a felony and, finally, attempted murder. Being that the stabbing occurred in the middle of the day and in a public place, it was caught on tape, and with multiple witnesses.

It’s a strange feeling, to know safety after recent months of being not-quite-sure where he was. Not-quite-sure if he’d reappear. Not-quite-sure what he meant by “I have no desire or intent” to move on.

While he's in custody, he can’t hurt anyone. But, of course, we’re all still hurting.

I’ve long been plagued by the thought that there’s an alternate reality — one in which he didn’t do it at all, or one in which he did it later, when I was old enough to remember. Or one in which he did it to me instead.

There is now a possibility that I may see my father outside a grainy mugshot — this time, in a courtroom, to deliver a statement before the judge who would determine his sentence, should he be found guilty.

I’m at once paralyzed by fear and excited at the possibility of justice, pondering what exactly I could say about the man who took so much from me.

I could explain how I take care of my mom now. How she has a standing doctor’s appointment once a month (plus three or four others, littered throughout the weeks). How I tell time by when she gets her pills: 8 AM, 3 PM, and 9 PM — something for pain, for nerve damage, for seizures, for depression.

Or how, as a little girl, I told my friends my mom could do a great trick — remove her right eye — and then I’d ask her to take out her prosthetic eye from its socket, while the other small children screamed in horror. Some cried.

I could explain how I see her every day but I don’t really know my mom — the person she is without the brain damage and the medications and the memory loss. How I’ve spent a lifetime trying to reconstruct a woman I can’t fully grasp.

And I could explain how I’ve never even spoken to my dad. Never so much as blinked in his direction, or breathed the same air. But I do know him.

I know that he isn’t sorry.

I know that his violence won’t abate.

I know that he’d do it again.

I know that he deserves a room with no windows, and no light at all.

Thank you for indulging me in this personal essay. I promise I’ll get back to design and thrifting content after this.

For more of the personal stuff, head to these two posts from the archives:

Finding Beauty in a Thrift Store

There is a fortune I have gotten no less than six times — one tucked away in fortune cookies that keeps making reappearances in my life again and again. “You find beauty where others see nothing unu…

I’ll leave you with this…

I love that your grandmother remained unbowed by what happened. She loved you and your mom fiercely, did what was necessary and refused to let violence define or control your lives. It also really underscores for me the necessity of Art as a mode of healing and defiance and explains why the “Art” of living is a serious and deep matter.

Breathtaking. Terrifying. I am so glad you are safe. I am so glad you are here to write these words, and all the others you share in this space and elsewhere. ❤️